Goethe’s Morphology and Study of Metamorphosis

Poet, Artist, and Natural Scientist

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749–1832) was not only a poet and statesman, but also a committed naturalist. His active interest in the sciences developed from the second half of the 1770s onwards; starting with geology and mineralogy, his path then led him to anatomy and botany, the theory of colours, and finally to the field of meteorology.

The Goethe Laboratory has been set up in the former chambers of the botanical garden’s inspector house. With the help of the architect Clemens Wenzeslaus Coudray Goethe had it rebuilt in 1825/26 and often stayed there when visiting Jena and the grounds of the botanical garden. The large and over 200-year-old Ginkgo tree in the garden was planted in his lifetime.

A cutout from the portrait of Goethe by Heinrich Christoph Kolbe: Goethe as poet and artist in front of Mount Vesuvius (1826). Photo: Anne Günther (University of Jena)

Image: Anne Günther (University of Jena)This life-size portrait of Goethe by the Düsseldorf-born painter Heinrich Christoph Kolbe was created between 1822 and 1826. It depicts the poet, artist and scientist at over 70 years of age amidst an Italian landscape. Mediterranean plants, antique ruins and Mount Vesuvius in the background of the painting allude to Goethe's areas of interest.

A verse from Goethe’s Maskenzug (1818) can be read in the small notebook: »Nicht vorbey ‒ Es muss erst frommen.« This roughly translates to »Not over yet! It must first bear fruit.«

Visitors to this exhibition also have the opportunity to watch their research “bear fruit” as they explore the exhibition, using their own hands and minds to gain valuable insight into Goethe’s own scientific efforts.

Membership certificate of the Societät für die gesammte Mineralogie zu Jena (Society of the Entirety of Mineralogy in Jena) founded in 1797 for Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel. In 1803 Goethe became president of the society.

Image: Friedrich-Schiller-Universität JenaGeology Room

Geology and Meteorology

The mineralogical collection of the University of Jena was always supported by Duke Carl August and Goethe.

Here Goethe often studied his favourite rock, granite. “Every journey into unknown mountains confirmed the old experience,” he wrote in 1785, ”that the highest and the deepest is granite, that this type of stone, which one now learned to know better and distinguish from others, is the foundation of our earth, on which all other diverse mountains are formed.” (Granite II, 1795)

The importance of the differentiating natural research and the developing scientific societies at the university is shown by the membership certificate of the philosopher Hegel, signed by the Bergrat Johann Georg Lenz: “The Ducal Jena Mineralogical Society hereby certifies that it has appointed Dr. Georg Wilhelm Hegel as honorary assessor by unanimous vote. Jena, January 30, 1804”

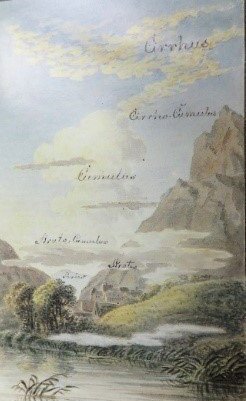

Cloud shapes according to Howard, board from the 1st volume of the journal "On Natural Science in General", 1820

Picture: Johann Wolfgang von GoetheGoethe not only intensively studied the formative processes of the earth's history, but also cloud formations and especially their transitions into one another. He designed the small table to enable the weather observers at the meteorological station in Jena to determine the most important cloud forms. Goethe adopted the cloud names defined by the English pharmacist Luke Howard - stratus, cumulus, nimbus and cirrus - into the German scientific language.

Anatomy Room

Anatomical Studies

Skulls and models from the university's anatomical collection illustrate Goethe's most important discovery in anatomy: the intermaxillary bone in humans. This bone carrying the incisors, known as os intermaxillare, is clearly visible in many mammals between the halves of the upper jaw, distinctly separated by bone sutures. In humans, however, these sutures are not normally visible, which is why leading anatomists in the 18th century regarded the small bone as a distinguishing feature between humans and animals.

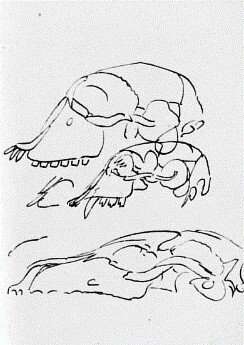

Goethe’s studies on the skull: Intermaxillary demonstration

Picture: Johann Wolfgang von GoetheDuring anatomical examinations with Jena professor Justus Loder, Goethe discovered traces of the intermaxillary bone on the human skull on 27 March 1784. His conclusion from this: It is not the presence of this bone, but its specific form that is the decisive difference between the various animal species, to which humans also belong anatomically. - That was still a bold assertion at the time!

On 27 March 1784, he excitedly informs his friend Johann Gottfried Herder:

»I have found - neither gold nor silver, but what gives me unspeakable joy - the os intermaxillare on man! [...] It should also make you very happy, because it is like the keystone to man, it is not missing, it is also there! But how!«

While working out his treatise on the intermaxillary bone, Goethe develops his method of series formation. He writes:

»What a gulf between the os intermaxillare of the tortoise and the elephant! And yet a series of forms can be placed between them that connect the two.«

Goethe had to experience his discovery being dismissed by the experts. However, this does not stop him from examining other bones and arranging them. In doing so, he lays the foundation for the science he calls »morphology«, which is dedicated to forms and changes in form within living nature.

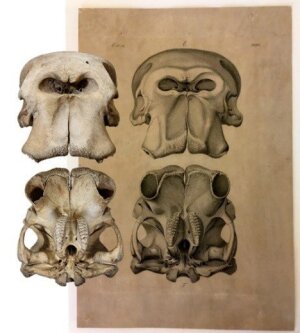

Drawings of the skull of the African elephant by Johann Christian Wilhelm Waitz, next to respective photos of the original.

Picture: Johann Christian Wilhelm WaitzJena's "Goethe Elephant" Skull

The largest original object in the exhibition is the skull of an African elephant from the 17th century. When the university's anatomical collections were established, it held a place of honour in the room of »mammals« from the early 1780s. For decades it slumbered in the attic of the Phyletic Museum in Jena. Now, newly restored, it can be displayed and appreciated in its importance for the process of discovery: Goethe himself studied this skull and its bone structures in detail and compared it with other elephant skulls. In discussions with Loder, he was also concerned with the question of whether the tusks are rooted in the premaxilla or in the upper jaw.

The skull of the African elephant served as a template for precise drawings that Johann Christian Wilhelm Waitz made on Goethe's behalf in Jena in 1784 (pictured right). Based on these drawings, the recovered skull could be clearly identified as a “Goethe elephant”.

Anatomical structures are also characterized by a certain mobility in their development. We recommend watching the educational video Morphogenesis of the elephant skull!

Botany Room

Botanical Classifications

Carl von Linné (1707-1778) gave many plants and animals the Latin names that are still used today and created an artificial system of plant identification. A herbarium cabinet in the tradition of the Swedish botanist allows visitors to classify herbarium sheets themselves according to his system and learn interesting facts about different plant species.

Although Linné's system proved to be efficient, the artificial classification ultimately failed to satisfy Goethe and his contemporaries. The Jena professor August Johann Georg Carl Batsch (1761-1802), founder and first director of the Botanical Garden, therefore developed a system that took into account the family or shape similarities of the plant genera. However, these natural »relationships« (»affinitates naturales«) can only be represented in a complex structure. In the future, parts of the system will be on display in the exhibition as a three-dimensional model.

Adam Immanuel Weise: August Johann Georg Carl Batsch,1802. Pencil and white highlights on paper on carton.

Picture: Adam WeiseOn the east side of the inspector's house, Batsch had flowerbeds planted according to the assumed order. These beds were reconstructed according to the original garden plan published by Batsch in 1795. Even after Batsch's death, Goethe adhered to this planting plan. Batsch's successors at the Botanic Garden, Franz Joseph Schelver (1778-1832) and Friedrich Siegmund Voigt (1781-1850), also worked intensively on Goethe's botanical concepts.

Since Darwin's theory of evolution (1859), similarities between plants have been understood as a possible order based on real descent. Following genetic studies, some botanical relationships that were assumed on the basis of external characteristics are currently being revised.

According to Goethe, the »simultaneous metamorphosis« can be seen in the juxtaposition of the different plant species. Plant and environment shape the plant forms. ‒ Goethe's ideas are still effective today.

The Metamorphosis of Plants

During his stay in Italy (1786-88), Goethe gained important insights into the plant world. The exotic vegetation, which he admired for the first time in September 1786 in the Botanical Gardens of Padua, awakened in him the idea »that all plant forms could perhaps be developed from one«. He later called this figure the »primordial plant« and finally the »symbolic plant«.

Zwergpalme (Chamaerops humilis)

Image: Lara DonnerGoethe clearly saw the metamorphosis of the leaves in Padua on a dwarf fan palm (Chamaerops humilis L.), the step sequence of which he had cut off and took back to Weimar as a »fetish« to keep. In the exhibition, a dwarf-fan palm from the Botanical Garden of the University of Jena commemorates this event.

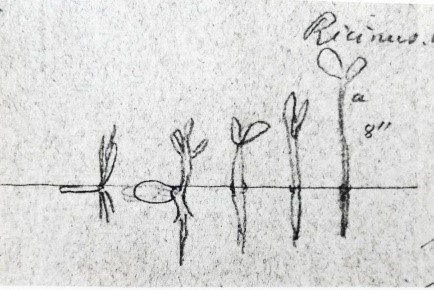

While the organs of vertebrates can be viewed and compared side by side, metamorphosis in the plant kingdom is a sequence of different leaf forms, from the cotyledons to the flower and fruit. In his Attempt to explain the metamorphosis of plants (1790), Goethe calls this a »successive metamorphosis«, similar to that of insects. If the individual growth stages are drawn or preserved, the leaf sequence can be reconstructed.

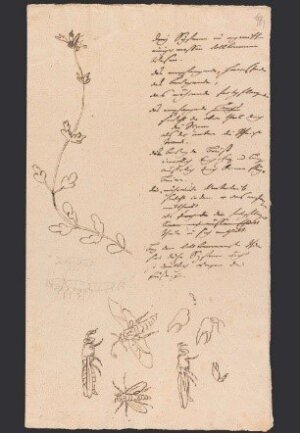

Drawing by Goethe on the theory of metamorphosis, showing a flowering plant with a typified sequence of leaves and several insects.

Picture: Johann Wolfgang von GoetheMorphology of Organic Bodies

When working on his theory of metamorphosis, Goethe not only used written notes, but also drawings with conspicuous frequency. This makes it possible to follow his morphological thinking as it developed. The sheet illustrated on the following page shows a flowering plant with a typified sequence of leaves and several insects. The »course of life« of insects is also, as Goethe pointed out, a »continual reshaping, to be seen with the eyes and grasped with the hands«. (Be sure to take a look into the first drawer to the left of the work table!)

The keywords on the right-hand half of the drawing state that three »systems« can be observed in »organic, reasonably perfect beings«, which are labelled »head«, »chest« and »abdomen«.

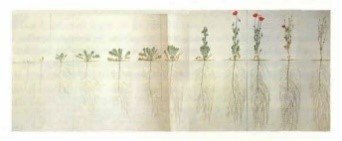

Following the germination and development of a plant is a school of morphological vision. Jochen Bockemühl and Ruth Richter's precise recording of the developmental stages of the red poppy, for example, gives us a deeper insight into the temporal process of growth. (below)

Developmental stages of the red poppy

Picture: Jochen Bockemühl und Ruth RichterIn his poems The Metamorphosis of Plants, Metamorphosis of Animals and Primal Words. Orphic, which can be seen and heard in the exhibition, Goethe applied the developmental principle of nature and the laws of morphology to human life as well. We recommend watching the Poetry film Metamorphoses.

Johann Christian Reinhart: Goethe and Schiller in conversation, pen and ink drawing 1804

Image: Johann Christian ReinhartExchange with Schiller about Plants and Colours

Friedrich Schiller (1759-1805) moved to Jena in 1789 without Goethe coming into closer contact with him. But on July 20, 1794, after a meeting of the Naturforschende Gesellschaft (Society for the Study of Natural Sciences), they got into a conversation about the metamorphosis of plants. This inspired Goethe to present his botanical ideas in more detail: Therefore he draws »a symbolic plant«. Schiller replies: »That is not an experience, that is an idea.«

The exchange that now began enabled both authors to become aware of their different views and opinions. Despite their differences, a fruitful working relationship was born, which soon included Goethe's work on colour theory.

Goethe sees colours as dynamic phenomena. He is convinced that they also follow the laws of polarity and intensification, which he sees at work in all of nature. The black and white figure on the south window allows you to undertake Goethe's most important experiments with the prism yourself, true to his statement to Eckermann on December 21, 1831, that the theory of colour »should not merely be read and studied, but should be undertaken.«

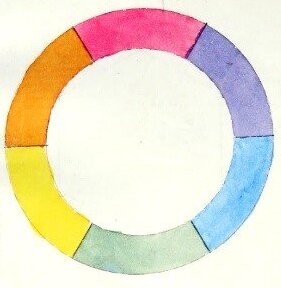

Six-part colour wheel

Picture: Johann Wolfgang von GoetheHis six-part colour wheel from 1794 is a representation of these laws. Goethe was also the first to explore the psychological effect of the different colours; for him, they are »deeds and sufferings of light«. The coloured glass panels based on Goethe's colour wheel allow a differently coloured view of the surroundings. Allow the atmospheric values of the individual colours have an effect on you!

(Text: Helmut Hühn and Margrit Wyder)